What better way to close out 2022 and start 2023 than with a story about cats?

“Life, With Cats” is the title story to my first collection of cat stories. Yes, there’s a second collection coming — Unexpected Cats — which is currently in the process of publication, but for right now, enjoy this story about a kitty who serves a very special purpose to people who need him the most.

Life, With Cats

Annie Reed

For Beansie.

The door of the viewing room shut behind Mellie with a solid thunk. The sound so unlike the whoosh and hiss of displaced air when the pressure doors on her ship sealed shut that she flinched.

She never flinched at anything. Just went to show how frayed her nerves were. She didn’t want to be in this room, in this city, on this planet, but she’d never forgive herself if she ignored her father’s one last wish like she’d ignored every other wish he’d ever had for her life.

Everything about this room was different from the ship she’d called home for the last ten years. Mellie was used to small spaces partitioned off by dull metal bulkheads studded with handholds on the floor and the ceiling as well as the walls. Artificial gravity was a dicey thing in space. Mellie had grown accustomed to walking so that one booted foot always remained in contact with the floor, even when the floor was a ceiling. The magnets in the soles of her boots kept her grounded no matter what.

She had to remind herself not to walk that way here. She’d already tripped once on the uneven ground outside the House of Memories. Inside, the carpet was so thick she’d felt a static charge from her shuffling, dragging gait raise the fine hair on her arms. Perhaps that was why the doors and walls and the few rows of bench seats in this room were made of wood.

The wood wasn’t the only thing that reminded her she was no longer on her ship.

Panels containing viewing screens lined the walls on all sides like windows. With the exception of the cockpit, Mellie’s ship had only small portholes in the exterior bulkhead. There wasn’t much to see in space except for long stretches of emptiness and the distant pinprick of stars. The screens in this room currently displayed an idealized Earth setting—towering trees surrounding a meadow of lush, green grass sprinkled with a kaleidoscope of wildflowers, with majestic, snow-capped mountains in the distance beneath a blue, cloudless sky.

This must have been what Earth looked like when her father was a child. Everything in this room was supposed to represent his memories. Perhaps that’s why a cat was curled up, apparently asleep, on one of the long wooden benches to her right.

Her father had always kept cats. Mellie had no affinity with animals. One of her crew had a holo of a dog in his cabin, like other crew displayed holos of family members they’d left planet side. The man had told her the dog was his only friend. Mellie had never quite understood. She supposed it was one of the failings that had kept her off deep-space missions. She could almost see the notation in her psych evaluation—lack of empathy for non-human species. Couldn’t have that attitude in potential first-contact situations.

She didn’t care. She’d made a life for herself in space, and in the process, left her father behind. It had taken six months for the news of his death to reach her, and another year for her to return to a place she no longer thought of as home to participate in honoring his life.

Had the cat belonged to her father? Who’d been taking care of it all this time? Mellie had been her father’s only child. Her mother had died when Mellie was still too young to fully understand what death meant. She’d sat with her father in another room like this while her mother’s life played out around them. She hadn’t recognized the youthful woman in the holos as her mother, but she’d known that the images made her father incredibly sad. She’d promised herself she’d never voluntarily step in another viewing room again, yet here she was. Her father had no other family save Mellie. Viewing his life and paying honor to all that he had been fell on her shoulders, whether she wanted that honor or not.

Mellie ignored the cat and sat on the first bench to the left. The wood was hard beneath the backs of her thighs, but hard in a different way than the cold metal benches on her ship. The bench could have been made of synth-wood, but when Mellie ran her fingertips over the surface, she felt minute, random imperfections—scratches and chips and gouges—no machine-made product could replicate. Modern, mass-produced fakery was all about removing imperfections. This room seemed to celebrate them.

She’d been instructed simply to say “Begin” when she was ready to view her father’s life. She’d promised herself she would say the word as soon as she sat down. She wanted to get this over and done with so she could get back to her ship. Even though she knew she was in an enclosed room, the illusion of wide-open green spaces and distant mountains created by the screens made her uneasy. Space was infinitely vaster than the fake landscape, but surrounded by her ship it was easy to ignore that vastness. In her ship, she felt cocooned. In this room, she felt exposed.

Something bumped against her leg. Mellie flinched again even as she looked down and saw the cat leaning against her. It had fur the color of the sandy ground outside. Its tail was long and thick like cabling. The cat had wrapped that long, thick tail around the back of Mellie’s calf.

The cat stayed like that, leaning its hip against Mellie’s leg, like it was waiting for something. Mellie didn’t know what it wanted. All she wanted was to make herself say the word “Begin,” but it seemed stuck in her throat.

The cat turned its head to look at Mellie over its shoulder. The cat’s eyes were deeper gold than its fur, its pupils thin black vertical slits in the bright artificial sunlight shining off the screens. Its ears were forward, but it looked worried somehow.

“I don’t know anything about cats,” Mellie said. “I don’t know what you want.”

The cat leaned harder against her leg.

Mellie dredged up a memory—her father sitting in an overstuffed chair in the last house where they’d lived together before Mellie left to go to flight school. They’d been arguing. They’d always been arguing in those days. Her father hadn’t wanted her to go. He’d thought flight school would be too hard on her. She’d told him she was tougher than she looked.

One of his cats, a fuzzy grey and white one with green eyes, had rubbed into her father’s leg. He’d reached down absentmindedly and scratched the cat on its back near the base of its tail. After a few moments, the cat had jumped up onto her father’s lap.

Their argument trailed off after that. The cat had curled up and gone to sleep in the crook of her father’s arm. Her father had told her he knew she could take care of herself, he just didn’t want to see her hurt. With the self-assurance of youth, she’d assured him no one could hurt her.

It had taken only six weeks at flight school before she’d been hurt. Women, especially short, slight women, weren’t pilot material, or so the upper classmen who’d attacked her said. Mellie never told her father about the hazing that had gone too far. She’d taken the pain and humiliation and used it the same way her ship used fuel. She hadn’t graduated at the top of her class, but she’d come close. Close enough to get on the short list for deep-space missions.

Right up until the final pre-mission psych evaluations.

Mellie reached one hand down toward the cat. It looked at her but made no move, hostile or otherwise, as she touched the fur on its back near its tail. She scratched it there, her fingertips feeling the strong muscle and hard bone beneath its skin. The cat shut its eyes. She heard a purr rumble softly in its throat.

“Begin,” Mellie said.

She hadn’t known quite what to expect. Her mother’s viewing had taken place in a darkened room. The holo images from her mother’s past had moved around the dark space like an entertainment vid. Mellie thought her father’s viewing might start the same way, with a darkening of the images on the window screens.

Instead, a holo of her father shimmered into existence at the front of the room. He looked the way he had the last time she’d seen him.

“Hello, sweetheart,” the holo said.

A cold, hard knot settled in the middle of her chest. He’d recorded a message for her.

Of course, he had. Her father hadn’t died suddenly, like her mother. He’d known he was dying. He’d had time.

Mellie wouldn’t have thought the sight of him could make her hurt so much. It had been years since she’d talked to him, even longer since he’d called her sweetheart.

“I know you don’t like these things,” the holo of her father said. “I’m not sure I want you seeing some of it. Guess I’m still trying to protect my little girl, even now. Not that you ever needed my protecting, but you see, I come from a different generation, and that’s what daddies did for their little girls. Daddies were the heroes, I guess is what I’m trying to say.”

In the holo image, her father looked uncomfortable. He didn’t have much hair left, but he ran a hand across the top of his nearly bald head like he was trying to brush hair he didn’t have off his forehead.

The cat jumped up on the bench next to Mellie, nudged her hand with its head, and she went back to scratching its back.

“I wasn’t a hero,” her father said. “Not even close.”

He raised his head and looked right at her. Mellie supposed the room was programed to direct the image at wherever she sat, but it still sent a chill down her spine.

“I just did what I had to do, and I lived with the consequences. I was never sorry, not for one damn minute, that I did what I did. That’s what I want you to come away with. I have no regrets about my life. I don’t want you to, either.” In the holo, her father cleared his throat. “So let’s get on with it, shall we?”

Now the room darkened. The holo of her father shimmered from sight, replaced by the entertainment-quality holos of a young man wearing a version of her father’s face.

The cat climbed onto Mellie’s lap. She felt the weight of it as it circled before lying down. She continued to scratch it, moving her hand to the side of its face. Its purr got louder.

Mellie watched, fascinated, as her father, the young man, left his own parents’ home. She saw him board a transport with other young men and a few young women. Saw them all disembark on a permacrete landing pad. A domed structure loomed overhead. Beyond the clear outer wall of the dome was the blackness of space.

Her father had been to space?

A building came into focus ahead. Mellie’s breath caught in her throat as she read the sign in front of the building.

Her father had not only been to space. He’d gone to flight school, just like she had, only decades earlier.

Why had he never told her?

In another few minutes, the reason became apparent.

Her father had come upon a hazing not that different from what Mellie had suffered through. A young woman, one of the flight cadets, had been attacked by two other trainees. Her father had fought with one of them, and when her father won, the other ran away.

All of them, including the woman and her father, had been expelled from the school. Mellie watched, as stunned as her father, when he opened the official notification. Her father hadn’t done anything wrong. He’d saved the woman, but his career as a pilot was over because he’d fought with the other cadet.

Mellie wondered why the woman had been expelled. Maybe her psych evaluation profiled her as damaged.

That would have happened to Mellie, too, if she’d reported her attack. She hadn’t. She’d kept what happened to herself and finished her training.

No wonder her father didn’t want her going away to flight school.

The rest of her father’s life played out in the viewing room. Mellie saw him meet her mother. Watched them fall in love. Get married. She saw when she joined their lives. How tiny she’d been then.

A long stretch of her father’s life was missing from his memories—the period immediately after her mother’s death. Had he excised those memories on purpose, or had his grief been so overwhelming that the power of it was more than the embedded chip that stored a person’s lifetime could handle? Mellie would never know.

When the replay of her father’s life resumed, Mellie herself dominated his memories. She relived her first date, her first serious boyfriend followed shortly by her first broken heart, all from her father’s point of view. She saw him waiting up for her, a cat curled in his lap, his hand stroking its fur. A sand-colored cat, not unlike the one curled in Mellie’s own lap, sat watching when the two of them argued, its golden eyes inscrutable. A brown cat with tiger stripes wound around her father’s ankles as he stood at the window of their house watching her leave on her way to flight school.

Then there were the years after she left. Mellie had given very little thought to her father after she’d left home, but he hadn’t forgotten her. Holos of her remained around the house. He celebrated her birthdays with a toast in her honor, just like he celebrated her mother’s. He met with friends, had dinner with a woman now and then, and always, there were the cats. One or two or three, the cats had been her father’s constant companions.

Mellie braced herself for memories of the last of her father’s life, but instead of seeing him old and sickly in a hospital ward, the memories winked out. The room brightened and the screens filled once again with the panoramic view of the Earth of her father’s youth.

That was it?

She hadn’t had a chance to say goodbye.

She’d thought the holo image of her father would reappear at the end of the memories. She wanted a chance to tell him she understood him now. She wanted to tell him that she wished…

She wished what? That he’d told her why he didn’t want her to go? Would that have made a difference? Back then, no. Mellie would have told him she was smarter than the woman who’d been in her father’s class. She would have told him she could take care of herself. Only now, with the weight of her own experiences, did the revelation make a difference.

Only now, when it was too late.

The heavy wooden door opened behind her. Mellie turned on the bench, jostling the cat still curled up on her lap. It made a small, distressed noise. The frown was back on its furry face.

Mellie rubbed behind its ears. “There’s nothing to worry about,” she said. “I’m sorry I moved so fast.”

An elderly man entered through the door. He was stoop-shouldered and walked with a cane, but he still had a full head of snow-white hair. Mellie realized he was one of the men she’d seen in her father’s memories, although he looked far older now.

“You knew my father,” she said.

The old man nodded. His eyes were dark and deep set, his skin creased with a myriad of lines and wrinkles, and it looked like it pained him to walk. Still, the smile he gave her seemed genuine. “He was my best friend for twenty years. That’s why he came to me about his viewing.”

“You own this place?” Mellie had wondered why her father chose this House of Memories. There were others closer to where her father had lived.

“My son and his grandson and I,” the old man said. “And before me, the business goes back to my great-great grandfather. In those days, we were called morticians. Now?” He shrugged. “Memory keepers. By the time my great-great grandson takes over, he’ll be called something else.”

If her father had completed his pilot’s training, he and Mellie would have been in the same business, too. If she even existed. Space pilots didn’t tend to settle down and raise families.

The cat hopped down off Mellie’s lap and trotted over to the old man. It wound its tail around the old man’s leg like it had with Mellie.

“He likes to give hugs,” the old man said. “I can’t bend down to scratch him like I used to, though.”

A few sand-colored hairs stuck to her flight jacket, the only jacket she owned these days. When she’d lived with her father, cat hair had been nothing but an annoyance, and more than once she’d wished he’d get rid of the cats. Now she thought she was beginning to understand why he kept them.

“That was nice of you to take the cat in,” she said.

The old man cocked his head a little to the side as if he didn’t understand.

“This was my father’s cat, wasn’t it?” she asked.

She could see understanding dawn. “No, he lives here,” the old man said. “Along with four more. Your dad suggested it. Said some people find comfort in animals. Said they fill up spaces people didn’t even know they had.”

Had her father needed spaces in his own life filled up? Mellie didn’t want to think too closely on that, not now and certainly not here. Later, when she was alone in the cabin on her ship, maybe then she could take that thought out again and examine it. Learn from it. If nothing else, she could take the tight, cold, aching feeling in her chest and use it to make herself better.

That’s how she filled the spaces in her life. That’s how she’d always filled the emptiness inside.

Mellie’s lap felt cold without the cat’s warmth. She couldn’t take a cat aboard her ship. Cats couldn’t walk with magnetic gravity boots, and she didn’t want one to get hurt when her ship shut down artificial gravity to conserve energy.

“You said you were my father’s friend?” she asked the old man.

He nodded. “For twenty years.”

Mellie got up off the wooden bench. “I’d like to take a holo of you.”

He gave her a quizzical look.

“I have no other family,” she said. “It’s for my cabin on my ship.”

He seemed to consider for a moment, then he smiled. “I’d be honored.”

He straightened his stooped shoulders and smoothed down the front of his jacket. Mellie switched on the recording device embedded in her flight jacket. A display appeared in the air in front of her. Mellie focused with her eyes, making sure the cat was in the picture. When she was satisfied, she blinked her eyes, capturing the shot. She’d download it as a holo once she got back to her ship.

Her vision blurred over for a moment right after she took the holo.

She had no other family. Her father was really gone.

“I have a copy for you,” the old man said.

Copying memories was illegal. The old man and his future generations could lose their license to operate.

“I can’t let you do that,” she said.

“Not the memories. The introduction. Your dad had me record that separately just so you could take it. If you want.”

Mellie didn’t have to think about it. She couldn’t have a cat to fill the empty spaces.

“Yes.” Mellie tried a tentative smile. The ache in her chest loosened.

“Good. Come back to the office with me and we’ll take care of the transfer.”

The old man turned around and headed out through the door. Mellie followed. The cat didn’t. Instead it jumped back on the bench where it had been sleeping when Mellie first came in the room. It didn’t curl up but stood looking at Mellie.

She lingered after the old man disappeared into the hallway outside the room. She held her hand out to the cat like she’d seen her father do with cats that were unfamiliar with him. The cat sniffed her hand, then rubbed the side of its face against her fingers. She rewarded it with a scratch behind its ears.

“Thank you,” she said.

The cat looked up at her. She didn’t think its expression was inscrutable. It looked pleased with itself for a job well done.

She’d put the holo of the old man and the cat in her cabin. When she was ready, she’d rewatch her father’s introduction. She might even take a holo from that to put up next to the one with the cat and the old man. She didn’t think her father would mind.

Her dad said cats filled the empty spaces. He’d been right as far as it went, but Mellie thought it was more than that. What really filled the empty spaces was family. It was time—it was long past time—that she acknowledged hers.

~~~~~~~~~

Life, With Cats

Copyright © 2022 by Annie Reed

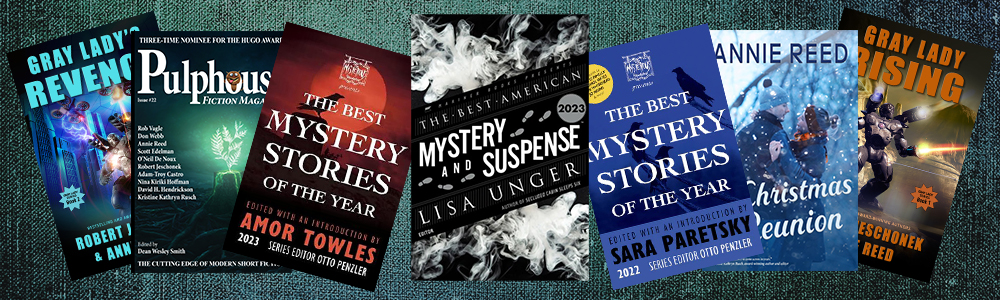

This story is part of the five-story collection Life With Cats, available at your favorite ebook distributor.